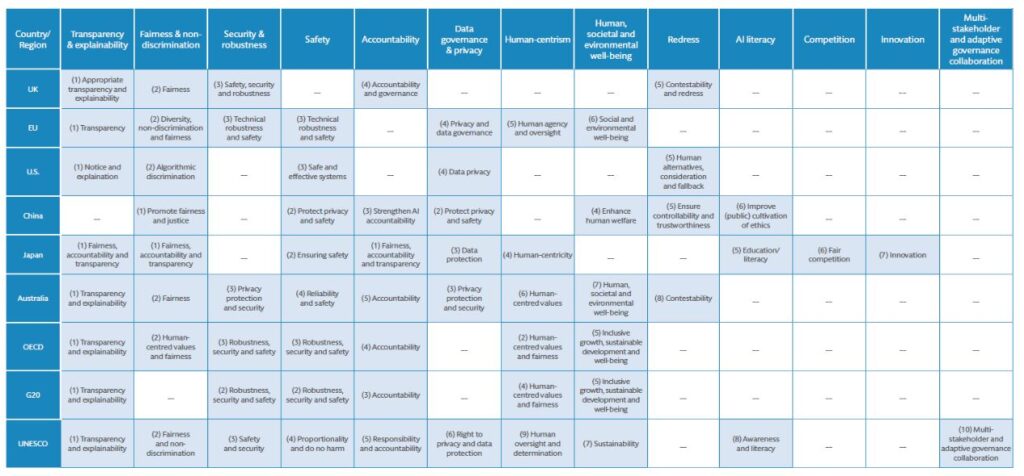

With the rapid rise of artificial intelligence, governments and policymakers are racing to release their own proposals on regulating the technology. Major jurisdictions including the EU, US, UK, and China are all at various stages in introducing new AI rules. And while there are differences between these proposals, our global survey demonstrates that there are also clear commonalties in the underlying principles that organisations are likely to be required to comply with. These similarities provide a useful starting point for the development of global AI governance standards

PIKOM Position for Inputs to the Plan updates on the Malaysian Personal Data Protection Act 2010 with General Data Protection Regulation 2016

The Personal Data Protection Act 2010 (PDPA) of Malaysia is set to be aligned with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union (EU). This is in line with the government’s commitment to ensuring that Malaysia has a strong data protection regime that is in line with international standards.

The PDPA and the GDPR are both comprehensive pieces of legislation that aim to protect the privacy of individuals. However, there are some key differences between the two laws. For example, the GDPR applies to all organizations that process personal data of individuals in the EU, regardless of where the organization is located. The PDPA, on the other hand, only applies to organizations that are located in Malaysia or that offer goods or services to individuals in Malaysia.

The alignment of the PDPA with the GDPR is expected to take place in two phases. The first phase, which is already underway, will involve the amendment of the PDPA to bring it more in line with the GDPR. The second phase, which is expected to be completed in 2023, will involve the establishment of a new data protection authority in Malaysia.

The alignment of the PDPA with the GDPR is a positive development for Malaysia. It will help to ensure that Malaysian organizations are compliant with international standards for data protection, and it will also help to protect the privacy of individuals in Malaysia.

Here are some of the key changes that are expected to be made to the PDPA as part of the alignment process:

- The definition of personal data will be expanded to include more types of information, such as biometric data and online identifiers.

- The requirements for obtaining consent will be strengthened.

- Individuals will be given more control over their personal data, such as the right to access, correct, and delete their personal data.

- Organizations will be required to report data breaches to the data protection authority.

- The penalties for non-compliance with the PDPA will be increased.

The alignment of the PDPA with the GDPR is a significant undertaking, but it is important for Malaysia to ensure that it has a strong data protection regime in place. The GDPR is one of the most comprehensive and stringent data protection laws in the world, and its alignment with the PDPA will help to protect the privacy of individuals in Malaysia.

General Comments on the Planned Update for PDPA

- Enforcement of PDPA

The Information Commissioner has a number of enforcement powers that they can use to ensure that organizations comply with information rights law under the amended PDPA. These powers include:

- Information notices: The Information Commissioner can issue an information notice to an organization requiring them to provide information about their data processing activities.

- Enforcement notices: The Information Commissioner can issue an enforcement notice to an organization requiring them to take specific steps to comply with information rights law.

- Penalty notices: The Information Commissioner can issue a penalty notice to an organization for failing to comply with information rights law. The maximum penalty for a breach of the Data Protection Act 2018 is £17.5 million, or 4% of the organization’s global turnover, whichever is higher.

- Prosecution: The Information Commissioner can bring a prosecution against an organization for failing to comply with information rights law.

The Information Commissioner will usually use their enforcement powers as a last resort. They will first try to resolve the issue with the organization through informal means, such as providing advice and guidance. However, if the organization is unwilling to comply with the law, the Information Commissioner may have to take enforcement action.

Here are some examples of enforcement actions that the Information Commissioner has taken in recent years:

- In 2021, the Information Commissioner issued a penalty notice to TikTok for £12.7 million for failing to comply with the Data Protection Act 2018. The Information Commissioner found that TikTok had failed to put in place adequate measures to protect the personal data of children under the age of 13.

- In 2019, the Information Commissioner issued a penalty notice to British Airways for £20 million for failing to protect the personal data of its customers. The Information Commissioner found that British Airways had failed to put in place adequate security measures to protect the personal data of its customers, which resulted in a data breach that affected over 500,000 people.

The Information Commissioner’s enforcement actions send a clear message to organizations that they must comply with information rights law. If organizations fail to comply with the law, they will face serious consequences.

- Citizen and Private Sector Consultation

Citizen and private sector consultation are a process of engaging with citizens and businesses to gather their input on a wide range of issues, from public policy to economic development. It is a critical tool for governments and businesses to ensure that they are making decisions that are in the best interests of all stakeholders.

There are many benefits to citizen and private sector consultation. It can help to:

- Improve the quality of decision-making by ensuring that all perspectives are considered.

- Build trust between governments and citizens, and between businesses and the communities they operate in.

- Increase public awareness of important issues.

- Foster innovation by tapping into the knowledge and expertise of citizens and businesses.

- Legitimize decisions by ensuring that they have the support of the people they affect.

There are a variety of ways to conduct citizen and private sector consultation. Some common methods include:

- Public meetings: These meetings provide an opportunity for citizens and businesses to come together and discuss issues face-to-face.

- Online surveys: These surveys can be used to gather feedback from a large number of people quickly and easily.

- Focus groups: These groups are made up of a small number of people who are selected to represent a cross-section of the population. They are led by a facilitator who helps to guide the discussion.

- Key informant interviews: These interviews are conducted with individuals who have specialized knowledge or experience on a particular issue.

The best way to conduct citizen and private sector consultation will vary depending on the issue at hand and the resources available. However, it is important to ensure that the process is inclusive and that all voices are heard.

Here are some tips for conducting successful citizen and private sector consultation:

- Be clear about the purpose of the consultation. What do you hope to achieve?

- Identify the key stakeholders who should be involved.

- Tailor the consultation methods to the specific issue and audience.

- Provide clear and concise information about the issue.

- Make it easy for people to participate.

- Be respectful of all viewpoints.

- Summarize the results of the consultation and take action on the feedback.

Citizen and private sector consultation are an essential tool for governments and businesses that want to make informed decisions and build trust with the people they serve. By following these tips, you can ensure that your consultation process is successful.

Comments on Known Pillars for the PDPA Updates

- The Right to Data Portability

The right to data portability is one of the eight fundamental rights that individuals have under the GDPR. It allows individuals to obtain the personal data that they have provided to a controller in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format. Individuals can then transmit this data to another controller, or request that the controller transmit it directly to another controller, without hindrance from the controller to which the personal data have been provided.

The right to data portability applies to personal data that individuals have provided to a controller, and that the controller is processing on the basis of the individual’s consent or in order to perform a contract with the individual. The right does not apply to personal data that is processed for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

To exercise their right to data portability, individuals must make a request to the controller. The request must be made in writing and must specify the personal data that the individual wants to receive. The controller must provide the personal data within one month of receiving the request.

The right to data portability is a powerful tool that allows individuals to control their personal data. It can be used to switch to a new service provider, to take advantage of new services, or to simply have a copy of their personal data for their own use.

Here are some examples of how the right to data portability can be used:

- An individual can use the right to data portability to switch to a new email provider. They can download their email history from their old provider and import it into their new provider.

- An individual can use the right to data portability to take advantage of new services that offer personalized recommendations. They can download their purchase history from an online retailer and use it to create a profile that can be used by other services to make recommendations.

- An individual can use the right to data portability to simply have a copy of their personal data for their own use. This could be useful if they want to keep a record of their personal data for their own records, or if they want to share it with a third party.

The right to data portability is a valuable tool that can be used to control personal data. It is important to be aware of this right and to use it when appropriate.

- Imposing Certain Obligations on Data Processors

Under the GDPR, a data processor is a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body that processes personal data on behalf of a controller. This means that the data processor does not determine the purposes and means of the processing, but rather carries out the processing activities in accordance with the instructions of the controller.

Data processors have a number of responsibilities under the GDPR, including:

- Processing personal data only on the instructions of the controller: Data processors must only process personal data in accordance with the instructions of the controller. They must not process personal data for any other purpose, without the prior consent of the controller.

- Ensuring the security of personal data: Data processors must take appropriate technical and organizational measures to ensure the security of personal data. This includes measures to prevent unauthorized access, use, disclosure, alteration or destruction of personal data.

- Keeping records of processing activities: Data processors must keep records of all processing activities carried out on behalf of the controller. These records must include information about the purposes of the processing, the categories of personal data processed, the recipients of the personal data, and the transfer of personal data to third countries or international organizations.

- Reporting data breaches to the controller: Data processors must report data breaches to the controller without undue delay. The data breach report must include information about the nature of the data breach, the number of individuals affected, the likely consequences of the data breach, and the measures taken to mitigate the impact of the data breach.

- Providing assistance to the controller: Data processors must provide assistance to the controller in responding to data subject requests, exercising data subject rights, and conducting data protection impact assessments.

Data processors that fail to comply with their obligations under the GDPR may be subject to fines of up to €20 million or 4% of their global annual turnover, whichever is higher.

Here are some examples of organizations that are typically considered to be data processors:

- Cloud computing providers

- IT service providers

- Website hosting providers

- Marketing agencies

- Research organizations

- Payment processors

If you are an organization that processes personal data on behalf of another organization, you are a data processor and you have a number of responsibilities under the GDPR. It is important to understand these responsibilities and to take steps to comply with them.

- Data Protection Officer (DPO)

The GDPR does not specify any specific qualifications for a DPO. However, the GDPR does require that DPOs have:

- Expertise in data protection law and practice: DPOs must have a deep understanding of data protection law and practice, including the GDPR. They must be able to advise organizations on how to comply with data protection law and to implement data protection measures.

- In-depth understanding of the organization’s data processing activities: DPOs must have a detailed understanding of the organization’s data processing activities. They must be able to identify and assess the risks to personal data that arise from the organization’s activities.

- Understanding of information technologies and data security: DPOs must have a good understanding of information technologies and data security. They must be able to advise organizations on how to protect personal data from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, alteration or destruction.

- Thorough knowledge of the organization and the business sector in which it operates: DPOs must have a thorough knowledge of the organization and the business sector in which it operates. They must be able to understand the organization’s needs and to advise it on how to comply with data protection law in a way that is practical and cost-effective.

- Ability to promote a data protection culture within the organization: DPOs must be able to promote a data protection culture within the organization. They must be able to raise awareness of data protection issues among employees and to help the organization to implement data protection measures.

In addition to these qualifications, the GDPR also recommends that DPOs have:

- At least three years of experience in data protection law and practice: This experience can be gained in a variety of roles, such as a lawyer, consultant, or auditor.

- A recognized qualification in data protection: There are a number of recognized qualifications in data protection, such as the Certified Information Privacy Professional (CIPP/E) and the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) Certification.

The GDPR does not require DPOs to be certified, but it does recommend that they have a recognized qualification in data protection. This is because certified DPOs have demonstrated their knowledge and skills in data protection law and practice.

If you are considering becoming a DPO, it is important to ensure that you have the necessary qualifications and experience. You can also get certified in data protection to demonstrate your knowledge and skills to potential employers.

- Outbound Data Transfer

The GDPR restricts the transfer of personal data outside of the European Economic Area (EEA) to countries that have been deemed to have an adequate level of data protection. This is to ensure that the level of protection of individuals afforded by the GDPR is not undermined.

There are a number of ways to transfer personal data outside of Malaysia in compliance with the GDPR. These include:

- Transfers to countries with an adequacy decision: The European Commission has made adequacy decisions for a number of countries, which means that these countries are considered to have an adequate level of data protection. This means that personal data can be transferred to these countries without any additional safeguards being put in place.

- Transfers to countries with binding corporate rules (BCRs): BCRs are a set of internal rules that are adopted by organizations that operate in multiple jurisdictions. BCRs provide a framework for transferring personal data from the EEA to countries that do not have an adequacy decision.

- Transfers with standard contractual clauses (SCCs): SCCs are a set of standard contractual clauses that can be used to transfer personal data from the EEA to countries that do not have an adequacy decision. SCCs provide a number of safeguards to protect the personal data that is transferred.

- Transfers to countries with a legal basis: In some cases, it may be possible to transfer personal data to a country that does not have an adequacy decision if there is a legal basis for the transfer. This could be the case if the transfer is necessary for the performance of a contract between the data subject and the controller, or if the transfer is necessary for the legitimate interests of the controller.

It is important to note that the GDPR does not allow for the transfer of personal data to countries that are subject to a generalized surveillance regime. This is because such countries are considered to pose a high risk to the fundamental rights of individuals.

If you are considering transferring personal data outside of the EEA, it is important to carefully consider the options available to you and to ensure that you comply with the GDPR. You should also seek advice from a data protection expert if you are unsure about the best way to proceed.

- Data Breach Notification

Under the GDPR, organizations must notify the supervisory authority and the affected individuals without undue delay if there has been a personal data breach that is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons.

The notification to the supervisory authority must include the following information:

- The name and contact details of the controller

- The nature of the personal data breach

- The number of data subjects affected

- The likely consequences of the personal data breach

- The measures taken or proposed to be taken to address the personal data breach, including measures to mitigate the possible negative effects

The notification to the affected individuals must include the following information:

- The name and contact details of the controller

- The nature of the personal data breach

- The likely consequences of the personal data breach

- The measures taken or proposed to be taken to address the personal data breach

- Information on how the affected individuals can obtain further information

The GDPR does not specify a timeframe for notifying the supervisory authority and the affected individuals of a personal data breach. However, it states that notification must be made without undue delay. This means that organizations should notify the supervisory authority and the affected individuals as soon as possible after becoming aware of the personal data breach.

If the personal data breach is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons, the organization must also take the following measures:

- Inform the affected individuals of the personal data breach without undue delay

- Take all reasonable steps to mitigate the possible negative effects of the personal data breach

- Report the personal data breach to the competent authorities in the Member State where the personal data breach occurred

The GDPR imposes strict penalties for organizations that fail to comply with the data breach notification requirements. Organizations can be fined up to €20 million or 4% of their global annual turnover, whichever is higher.

It is important for organizations to have a plan in place for responding to personal data breaches. This plan should include procedures for:

- Detecting and reporting personal data breaches

- Notifying the supervisory authority and the affected individuals

- Mitigating the possible negative effects of the personal data breach

- Reporting the personal data breach to the competent authorities

By having a plan in place, organizations can help to ensure that they are prepared to respond to personal data breaches in a timely and effective manner.

Additional Inputs to the PDPA Update

- The PDPA should be applied to Federal Government, State Government, and entities conducting non-commercial activity.

I agree with the statement that the PDPA should be applied to Federal Government, State Government, and entities conducting non-commercial activity.

The PDPA is a comprehensive piece of legislation that aims to protect the privacy of individuals. However, it currently only applies to organizations that are located in Malaysia or that offer goods or services to individuals in Malaysia. This means that the PDPA does not apply to the Federal Government, the State Government, or entities conducting non-commercial activity.

I believe that the PDPA should be applied to all organizations, regardless of their location or the nature of their activities. This is because all organizations collect and process personal data, and all individuals have a right to privacy. The Federal Government, the State Government, and entities conducting non-commercial activity are no different. They should all be held accountable for their handling of personal data.

There are a number of reasons why the PDPA should be applied to the Federal Government, the State Government, and entities conducting non-commercial activity. First, these organizations collect and process a significant amount of personal data. For example, the Federal Government collects personal data on all Malaysian citizens, including their names, addresses, and birth dates. The State Governments also collect personal data on their citizens, and entities conducting non-commercial activity often collect personal data on their customers and employees.

Second, these organizations have a great deal of power over individuals. The Federal Government can make laws, the State Governments can enforce laws, and entities conducting non-commercial activity can control access to goods and services. This power gives these organizations the potential to misuse personal data, and it is important to have safeguards in place to protect individuals.

Third, these organizations are often trusted by individuals. Individuals often believe that the Federal Government, the State Governments, and entities conducting non-commercial activity will protect their personal data. This trust is important, and it should not be abused.

I believe that the PDPA is a good piece of legislation, but it needs to be applied to all organizations, regardless of their location or the nature of their activities. This will help to protect the privacy of individuals and it will ensure that all organizations are held accountable for their handling of personal data.

- Processing of personal data in cloud computing.

The processing of personal data in cloud computing is a complex issue. On the one hand, cloud computing can offer a number of benefits for organizations that process personal data. For example, cloud computing can help organizations to:

- Save money on IT costs

- Improve scalability and flexibility

- Increase agility and responsiveness

- Reduce the need for on-premises infrastructure

On the other hand, there are also a number of risks associated with the processing of personal data in cloud computing. For example, cloud computing providers may have access to personal data, and they may be located in countries with weaker data protection laws.

The PDPA applies to the processing of personal data in cloud computing. This means that organizations that process personal data in the cloud must comply with the PDPA’s requirements.

Here are some of the key PDPA requirements that organizations need to consider when processing personal data in the cloud:

- Consent: Organizations must obtain consent from individuals before they can process their personal data.

- Security: Organizations must take appropriate technical and organizational measures to protect personal data from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, alteration, or destruction.

- Transfers of personal data: Organizations must only transfer personal data to countries that have adequate data protection laws.

- Data breach notification: Organizations must notify the PDPA if there is a data breach that is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of individuals.

Organizations that process personal data in the cloud should carefully consider the PDPA requirements and take steps to comply with them. This will help to protect the privacy of individuals and to avoid penalties from the PDPA.

Here are some additional tips for organizations that process personal data in the cloud:

- Choose a cloud provider that has a strong commitment to data protection.

- Review the cloud provider’s privacy policy and terms of service.

- Encrypt personal data before it is transferred to the cloud.

- Use strong passwords and multi-factor authentication.

- Monitor the cloud environment for security threats.

- Test and audit the cloud environment regularly.

- Have a plan for responding to data breaches.

By following these tips, organizations can help to protect the privacy of individuals and to comply with the PDPA when processing personal data in the cloud.

- Disclosure of data to government agencies (regulators, law enforcement, etc.)

The GDPR contains a number of exemptions that organizations can rely on to avoid compliance with certain provisions of the regulation. These exemptions are designed to ensure that the GDPR does not place an undue burden on organizations and that it does not interfere with legitimate activities.

Some of the most common GDPR exemptions include:

- Processing personal data for archiving purposes in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller: This exemption applies to organizations that process personal data for archiving purposes in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller. For example, this exemption could be used by government agencies that process personal data for the purposes of public records management.

- Processing personal data for scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes: This exemption applies to organizations that process personal data for scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes. This exemption is subject to a number of conditions, including the requirement that the processing must be carried out in accordance with data protection principles and that the results of the research must not be used to identify individuals.

- Processing personal data that is made public by the data subject: This exemption applies to organizations that process personal data that has been made public by the data subject. For example, this exemption could be used by organizations that publish personal data on social media or in news articles.

- Processing personal data that is necessary for the performance of a contract between the data subject and the controller or in order to take steps at the request of the data subject prior to entering into a contract: This exemption applies to organizations that process personal data that is necessary for the performance of a contract between the data subject and the controller or in order to take steps at the request of the data subject prior to entering into a contract. For example, this exemption could be used by organizations that process personal data to provide products or services to customers.

It is important to note that the GDPR exemptions are not exhaustive and that there may be other exemptions that apply in specific circumstances. If you are unsure whether an exemption applies to your organization, you should seek advice from a data protection expert.

In addition to the exemptions listed above, the GDPR also contains a number of derogations that organizations can rely on to avoid compliance with certain provisions of the regulation. Derogations are different from exemptions in that they are not absolute and can only be used in certain circumstances.

Some of the most common GDPR derogations include:

- Derogations for processing personal data in the public interest: This derogation allows organizations to process personal data in the public interest without the consent of the data subject, provided that the processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

- Derogations for processing personal data for the purposes of legitimate interests: This derogation allows organizations to process personal data for their legitimate interests, provided that the processing does not adversely affect the interests or fundamental rights of the data subject.

- Derogations for processing personal data in the context of employment: This derogation allows organizations to process personal data of their employees in the context of employment, provided that the processing is necessary for the purposes of the employment relationship.

It is important to note that GDPR derogations are subject to a number of conditions and must be used in a proportionate manner. If you are unsure whether a derogation applies to your organization, you should seek advice from a data protection expert.

The GDPR exemptions and derogations are complex and it is important to carefully consider all of the options available to you before relying on them. If you are unsure whether an exemption or derogation applies to your organization, you should seek advice from a data protection expert.

- Simplify and standardize consent request for data subjects.

- Consent is a key principle of the GDPR. It means that organizations must obtain the consent of individuals before they can process their personal data. Consent must be freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous. It must also be given for a specific purpose.

There are a few exceptions to the consent requirement under the GDPR. For example, organizations can process personal data without consent if it is necessary for the performance of a contract, or if it is necessary for the purposes of legitimate interests. However, organizations must always weigh the interests of the individual against their own interests when relying on an exception to the consent requirement.

There are a number of things that organizations can do to ensure that they obtain valid consent from individuals. These include:

- Making sure that the consent is freely given: Individuals must be able to give their consent freely, without any pressure or coercion.

- Making sure that the consent is specific: Individuals must be able to understand what they are consenting to. The consent must be specific to the processing activity that is being carried out.

- Making sure that the consent is informed: Individuals must have all of the information they need to make an informed decision about whether to consent. This includes information about the purpose of the processing, the types of personal data that will be processed, and the rights of the individual.

- Making sure that the consent is unambiguous: The consent must be clear and unambiguous. Individuals must be able to understand that they are giving their consent to the processing of their personal data.

If you are an organization that processes personal data, you should carefully consider the consent requirements under the GDPR and take steps to ensure that you obtain valid consent from individuals.

Here are some additional tips for obtaining valid consent under the GDPR:

- Use clear and plain language: The consent must be written in clear and plain language that is easy for individuals to understand.

- Use opt-in consent: Individuals should be able to opt in to the processing of their personal data, rather than having to opt out.

- Make it easy to withdraw consent: Individuals should be able to withdraw their consent easily and at any time.

- Keep records of consent: Organizations should keep records of the consent that they have obtained from individuals. This will help to demonstrate that they have complied with the GDPR’s consent requirements.

- The GDPR sets out specific rules for the processing of personal data of children under the age of 16. Under the GDPR, children are considered to be “data subjects” and their personal data is protected by the same rights as the personal data of adults. However, the GDPR also recognizes that children may not be as aware of their data protection rights as adults, and may be more vulnerable to harm from the processing of their personal data.

As a result, the GDPR imposes additional requirements on organizations that process the personal data of children. These requirements include:

- Obtaining parental consent: Organizations must obtain the consent of a parent or legal guardian before processing the personal data of a child under the age of 16. This consent must be given in a clear and explicit manner, and it must be specific to the processing activity that is being carried out.

- Providing information to children: Organizations must provide children with clear and age-appropriate information about the processing of their personal data. This information must be provided in a way that children can understand.

- Giving children the right to withdraw consent: Children have the right to withdraw their consent to the processing of their personal data at any time. Organizations must make it easy for children to withdraw their consent, and they must stop processing the personal data of the child once the consent has been withdrawn.

- Taking additional safeguards: Organizations must take additional safeguards when processing the personal data of children. These safeguards may include:

- Obtaining parental consent for specific processing activities that are considered to be riskier, such as the processing of sensitive personal data or the use of personal data for marketing purposes.

- Providing children with more control over their personal data, such as the right to access, correct, or delete their personal data.

- Making it easier for children to withdraw their consent.

The GDPR requirements for the processing of children’s personal data are designed to protect children from harm and to ensure that their rights are respected. If you are an organization that processes the personal data of children, you should carefully consider these requirements and take steps to comply with them.

- Data Privacy Impact Assessment (DPIA).

A data privacy impact assessment (DPIA) is a process that organizations can use to identify and assess the risks to personal data arising from their processing activities. The DPIA is a key requirement of the GDPR and it is designed to help organizations comply with the GDPR’s data protection principles.

The DPIA process should be carried out before any new processing activity is undertaken, or when there are significant changes to an existing processing activity. The DPIA should be documented and it should be kept up-to-date.

The DPIA should include the following steps:

- Identify the purpose of the processing activity: The first step in the DPIA process is to identify the purpose of the processing activity. This will help to determine the types of personal data that will be processed and the risks that may arise from the processing.

- Identify the data subjects: The next step is to identify the data subjects whose personal data will be processed. This will help to assess the potential impact of the processing on the data subjects.

- Identify the personal data that will be processed: The DPIA should identify the types of personal data that will be processed. This will help to assess the sensitivity of the data and the potential risks that may arise from the processing.

- Identify the risks to the data subjects: The DPIA should identify the risks to the data subjects arising from the processing activity. This includes risks to the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of the personal data.

- Evaluate the risks: The DPIA should evaluate the risks to the data subjects and determine whether the risks are high, medium, or low.

- Implement measures to mitigate the risks:** The DPIA should implement measures to mitigate the risks to the data subjects. These measures should be proportionate to the risks and they should be documented.

- Monitor and review the DPIA:** The DPIA should be monitored and reviewed on a regular basis to ensure that it is still accurate and up-to-date.

The DPIA is a complex process, but it is an important tool that organizations can use to comply with the GDPR and to protect the privacy of data subjects.

Here are some of the benefits of conducting a DPIA:

- It can help organizations to identify and assess the risks to personal data arising from their processing activities.

- It can help organizations to implement measures to mitigate the risks to personal data.

- It can help organizations to comply with the GDPR’s data protection principles.

- It can help organizations to demonstrate their commitment to data protection to data subjects and regulators.

If you are considering conducting a DPIA, it is important to seek advice from a data protection expert. A data protection expert can help you to understand the DPIA requirements and to conduct the DPIA in a compliant manner.

- Civil litigation against data user

The GDPR allows individuals to bring civil litigation against organizations that have violated their data protection rights. This is a powerful tool that individuals can use to hold organizations accountable for their actions and to seek compensation for the harm that they have suffered.

To bring a civil litigation case under the GDPR, individuals must first make a complaint to the supervisory authority in the Member State where the organization is located. The supervisory authority will then investigate the complaint and decide whether to take enforcement action against the organization. If the supervisory authority does not take enforcement action, individuals may then bring a civil litigation case against the organization in the national courts.

Individuals who bring civil litigation cases under the GDPR can seek compensation for a range of damages, including:

- Material damages: This includes financial losses that individuals have suffered as a result of the data breach, such as the cost of replacing stolen credit cards or the cost of repairing damage to a computer system.

- Non-material damages: This includes emotional distress, loss of privacy, and damage to reputation.

The amount of compensation that individuals can recover in civil litigation cases under the GDPR is not capped. This means that individuals can potentially recover very large sums of money if they have suffered significant harm as a result of a data breach.

The GDPR also allows individuals to seek injunctive relief in civil litigation cases. This means that individuals can ask the court to order the organization to stop processing their personal data or to take other steps to protect their data.

Civil litigation cases under the GDPR can be complex and expensive. However, they are a powerful tool that individuals can use to hold organizations accountable for their actions and to seek compensation for the harm that they have suffered.

Here are some examples of civil litigation cases that have been brought under the GDPR:

- In 2021, a French court ordered Google to pay €100,000 to a woman who had her personal data leaked in a data breach.

- In 2020, a German court ordered Facebook to pay €600,000 to a man who had his personal data leaked in a data breach.

- In 2019, a British court ordered British Airways to pay £183 million to customers who had their personal data leaked in a data breach.

These cases demonstrate that the GDPR can be a powerful tool for individuals who have suffered harm as a result of a data breach. If you have had your personal data breached, you should consider bringing a civil litigation case against the organization that was responsible for the breach.

Additional and/or Undocumented Points made during the meeting Comments

Accountability Framework

What is accountability?

Accountability is one of the key principles in data protection law – it makes you responsible for complying with the legislation and says that you must be able to demonstrate your compliance.

It’s a real opportunity to show that you set high standards for privacy and lead by example to promote a positive attitude to data protection across your organisation.

Accountability enables you to minimise the risks of what you do with personal data by putting in place appropriate and effective policies, procedures and measures. These must be proportionate to the risks, which can vary depending on the amount of data being handled or transferred, its sensitivity and the technology you use.

Regulators, business partners and individuals need to see that you are managing personal data risks if you want to secure their trust and confidence. This can enhance your reputation and give you a competitive edge, helping your business to thrive and grow.

How can I use the framework?

The framework is an opportunity for you to assess your organisation’s accountability. Depending on your circumstances, you may use it in different ways. For example, you may want to:

- create a comprehensive privacy management programme;

- check your existing practices against the ICO’s expectations;

- consider whether you could improve existing practices, perhaps in specific areas;

- understand ways to demonstrate compliance;

- record, track and report on progress; or

- increase senior management engagement and privacy awareness across your organisation.

- The framework is divided into 10 categories, Leadership and oversight, Policies and procedures, Training and awareness, Individuals’ rights, Transparency, Records of processing and lawful basis, Contracts and data sharing, Risks and data protection impact assessments (DPIAs), Records management and security, and Breach response and monitoring complemented with Case studies.

For example, ‘Leadership and oversight’. Selecting a category will display our key expectations and a bullet-pointed list of ways you can meet our expectations. These are the most likely ways to meet our expectations, but they are not exhaustive. You may meet our expectations in slightly different or unique ways.

You can demonstrate the ways you are meeting our expectations with documentation, but accountability is also about what you actually do in practice so you should also review how effective the measures are.

Accountability is not about ticking boxes. While there are some accountability measures that you must take, such as conducting a data protection impact assessment for high-risk processing, there isn’t a ‘one size fits all’ approach.

You will need to consider your organisation and what you are doing with personal data in order to manage personal data risks appropriately. As a general rule, the greater the risk, the more robust and comprehensive the measures in place should be.

1. EU General Data Protection Regulation

2. What’s Data Privacy Law in Your Country?

3. How to Conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment

4. An Interview with MDEC Discussing Artificial Intelligence in Malaysia

5. ICO Publishes AI Auditing Framework Draft Guidance

6. Explaining AI Decisions

7. Privacy Statement

EU General Data Protection Regulation

Chapter 1 General Provisions

- Article 1

Subject-matter and objectives

This Regulation contains rules on processing personal data and the free movement of personal data to protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons and their right to protection of personal data

- Article 2

Material Scope

This Regulation applies to the processing of personal data which form part of a filing system.

- Article 3

Territorial Scope

This Regulation applies to controllers and processors in the Union and controllers or processors not in the Union if they process personal data of data subjects who live in the Union.

- Article 4

Definitions

This Article contains 26 essential definitions.

Chapter 2 Principles

This chapter outlines the rules for processing and protecting personal data.

- Article 5

Principles relating to processing of personal data

Personal data shall be processed lawfully, fairly, and in a transparent manner; collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes; be adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary; etc.

- Article 6

Lawfulness of processing

There are six reasons that make processing lawful if at least one is true (e.g. data subject has given consent, processing is necessary for the performance of a contract, etc).

- Article 7

Conditions for Consent

When processing is based on consent, whoever controls the personal data must prove consent to the processing, and the data subject can withdraw consent at any time.

- Article 8

Conditions applicable to child’s consent in relation to information societal services

Information society services can process personal data of a child if the child is over 16. If the child is under 16, the legal guardian must consent.

- Article 9

Processing special categories of personal data

Processing personal data revealing race, political opinions, religion, philosophy, trade union membership, genetic data, health, sex life, and sexual orientation is prohibited unless the subject gives explicit consent, it’s necessary to carry out the obligations of the controller, it’s necessary to protect the vital interests of the data subject, etc.

- Article 10

Processing personal data related to criminal convictions and offenses

Processing personal data related to criminal convictions can only be carried out by an official authority or when Union or Member State law authorizes the processing.

- Article 11

Processing which does not require identification

The controller does not need to get or process additional information to identify the data subject if the purpose for which the controller processes data does not require the identification of a data subject.

Chapter 3 Rights of The Data Subjects

This chapter discusses the rights of the data subject, including the right to be forgotten, right to rectification, and right to restriction of processing.

Section 1 Transparency and modalities

- Article 12

Transparent information, communications, and modalities for the exercise of the rights of the data subject

When necessary, the controller must provide information in a concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language, and the controller needs to provide information on action taken on request by and to the data subject within one month. Page Break

Section 2 Information and access to personal data

- Article 13

Information to be provided where personal data are collected from the data subject

When personal data is collected from the data subject, certain information needs to be provided to the data subject.

- Article 14

Information to provide to the data subject when personal data has not been obtained from data subject

When personal data is not obtained from the data subject, the controller has to provide the data subject with certain information.

- Article 15

Right of access by the data subject

The data subject has a right to know whether their personal data is being processed, what data is being processed, etc.

Section 3 Rectification and Erasure

- Article 16

Right to rectification

The data subject can require the controller to rectify any inaccurate information immediately.

- Article 17

Right to be forgotten

In some cases, the data subject has the right to make the controller erase all personal data, with some exceptions.

- Article 18

Right to restriction of processing

In some cases, the data subject can restrict the controller from processing.

- Article 19

Notification obligation regarding rectification or erasure of personal data or restriction of processing

The controller has to notify recipients of personal data if that data is rectified or erased.

- Article 20

Right to data portability

The data subject can request to receive their personal data and give it to another controller or have the current controller give it directly to another controller.

Section 4 Right to Object and Automated Individual decision-making

- Article 21

Right to Object

Data subjects have the right to object to data processing on the grounds of his or her personal situation.

- Article 22

Automated individual decision-making, including profiling

Data subjects have the right not to be subjected to automated individual decision-making, including profiling.

Section 5 Restrictions

- Article 23

Restrictions

Union or Member State law can restrict the rights in Articles 12 through 22 through a legislative measure.

Chapter 4 Controller and Processor

This chapter covers the general obligations and necessary security measures of data controllers and processors, as well as data protection impact assessments, the role of the data protection officer, codes of conduct, and certifications.

Section 1 General Obligations

- Article 24

Responsibility of the Controller

The controller has to ensure that processing is in accordance with this Regulation.

- Article 25

Data protection by design and by default

Controllers must implement data protection principles in an effective manner and integrate necessary safeguards to protect rights of data subjects.

- Article 26

Joint Controllers

When there are two or more controllers, they have to determine their respective responsibilities for compliance.

- Article 27

Representatives of controllers or processors not established in the Union

When the controller and processor are not in the Union, in most cases they have to establish a representative in the Union.

- Article 28

Processor

When processing is carried out on behalf of a controller, the controller can only use a processor that provides sufficient guarantees to implement appropriate technical and organizational measures that will meet GDPR requirements.

- Article 29

Processing under the authority of the controller or processor

Processors can only process data when instructed by the controller.

- Article 30

Records of Processing Activities

Each controller or their representatives needs to maintain a record of processing activities and all categories of processing activities.

- Article 31

Cooperation with the supervisory authority

The controller and processor have to cooperate with supervisory authorities.

Section 2 Security of personal data

- Article 32

Security of processing

The controller and processor must ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk.

- Article 33

Notification of a personal data breach to the supervisory authority

In the case of a breach, the controller has to notify the supervisory authority within 72 hours, unless the breach is unlikely to result in risk to people. And the processor needs to notify the controller immediately.

- Article 34

Communication of a personal data breach to the data subject

When a breach is likely to cause risk to people, the controller has to notify data subjects immediately.

Section 3 Data protection impact assessment and prior consultation

- Article 35

Data protection impact assessment

When a type of processing, especially with new technologies, is likely to result in a high risk for people, an assessment of the impact of the processing needs to be done.Page Break

- Article 36:

Prior consultation

The controller needs to consult the supervisory authority when an impact assessment suggests there will be high risk if further action is not taken. The supervisory authority must provide advice within eight weeks of receiving the request for consultation.

Section 4 Data protection officer

- Article 37

Designation of the data protection officer

The controller and processor must designate a data protection officer (DPO) if processing is carried out by a public authority, processing operations require the systematic monitoring of data subjects, or core activities of the controller or processor consist of processing personal data relating to criminal convictions or on a large scale of special categories of data pursuant to Article 9.

- Article 38

Position of the data protection officer

The DPO must be involved in all issues which relate to the protection of personal data. The controller and processor must provide all necessary support for the DPO to do their tasks and not provide instruction regarding those tasks.

- Article 39

Tasks of the data protection officer

The DPO must inform and advise the controller and processor and their employees of their obligations, monitor compliance, provide advice, cooperate with the supervisory authority, and act as the contact point for the supervisory authority.

Section 5 Codes of conduct and certification

- Article 40

Codes of conduct

Member States, the supervisory authorities, the Board, and the Commission shall encourage the drawing up of codes of conduct intended to contribute to the proper application of the GDPR.

- Article 41

Monitoring of approved codes of conduct

A body with adequate expertise in the subject-matter and is accredited to do so by the supervisory authority can monitor compliance with a code of conduct. Page Break

- Article 42

Certification

Member States, the supervisory authorities, the Board, and the Commission shall encourage the establishment of data protection certification mechanisms to demonstrate compliance.

- Article 43

Certification bodies

Certification bodies accredited by Member States can issue and renew certifications.

Chapter 5 Transfers of Personal Data to Third Countries or International Organisations

This chapter provides the rules for transferring personal data that is undergoing or will undergo processing outside of the Union.

- Article 44

General principle for transfers

Controllers and processors can only transfer personal data if they comply with the conditions in this chapter.

- Article 45

Transfers on the basis of an adequacy decision

A transfer of personal data to a third country or international organization can occur if the Commission has decided the country or organization can ensure an adequate level of protection.

- Article 46

Transfers subject to appropriate safeguards

If the Commission has decided it can’t ensure an adequate level of protection, a controller or processor can transfer personal data to a third country or organization if it has provided appropriate safeguards.

- Article 47

Binding Corporate rules

The supervisory authority will approve binding corporate rules in accordance with the consistency mechanism in Article 63.

- Article 48

Transfers or disclosures not authorized by Union law

Any decision by a court or administrative authority in a third country to transfer or disclose personal data is only enforceable if the decision is based on an international agreement.

- Article 49

Derogations for specific situations

If there is no adequacy decision (Article 45) or appropriate safeguards, a transfer of personal data to a third country or organization can only happen if one of seven certain conditions are met.

- Article 50

International cooperation for the protection of personal data

The Commission and supervisory authority have to do their best to further cooperation with third countries and international organizations.

Chapter 6 Independent Supervisory Authority

This chapter requires that each Member State have a competent supervisory authority with certain tasks and powers.

Section 1 Independent status

- Article 51

Supervisory authority

Each Member state has to supply at least one independent public authority to enforce this regulation.

- Article 52

Independence

Each supervisory authority has to act with complete independence, and its members have to remain free from external influence.

- Article 53

General conditions for the members of the supervisory authority

Member states need to appoint members of the supervisory authority in a transparent way, and each member must be qualified.

- Article 54

Rules on the establishment of the supervisory authority

Each Member State needs to provide, in law, the establishment of each supervisory authority, qualifications for members, rules for appointment, etc.

Section 2 Competence, tasks, and powers

- Article 55

Competence

Each supervisory authority must be competent to perform the tasks in this Regulation.

- Article 56

Competence of the lead supervisory authority

The supervisory authority of a controller or processor that is doing cross-border processing will be the lead supervisory authority.

- Article 57

Tasks

In its territory, each supervisory authority will monitor and enforce this Regulation, promote public awareness, advise the national government, provide information to data subjects, etc.

- Article 58

Powers

Each supervisory will have investigative, corrective, authorization, and advisory powers.

- Article 59

Activity Report

Each supervisory authority must write an annual report on its activities.

Chapter 7 Co-operation and Consistency

This chapter outlines how supervisory authorities will cooperate with each other and ways they can remain consistent when applying this Regulation and defines the European Data Protection Board and its purpose.

Section 1 Cooperation

- Article 60

Cooperation between the lead supervisory authority and the other supervisory authorities concerned

The lead supervisory authority will cooperate with other supervisory authorities to attain information, mutual assistance, communicate relevant information, etc.

- Article 61

Mutual assistance

Supervisory authorities must provide each other with relevant information and mutual assistance in order to implement and apply this regulation.

- Article 62

Joint operations of supervisory authorities

Where appropriate, supervisory

authorities will conduct joint operations.

Section 2 Consistency

- Article 63

Consistency mechanism

For consistent application of this Regulation, supervisory authorities will cooperate with each other and the Commission through the consistency mechanism in this section.

- Article 64

Opinion of the Board

If a supervisory authority adopts any new measures, the Board will issue an opinion on it.

- Article 65

Dispute resolution by the Board

The Board has the power to resolve disputes between supervisory authorities.

- Article 66

Urgency Procedure

If there is an urgent need to act to protect data subjects, a supervisory authority may adopt provisional measures for legal effects that do not exceed three months.

- Article 67

Exchange of information

The Commission may adopt implementing acts in order to specify the arrangements for the exchange of information between supervisory authorities.

Section 3 European data protection board

- Article 68:

European Data Protection Board

The Board is composed of the head of one supervisory authority from each Member state.

- Article 69

Independence

The Board must act independently when performing its tasks or exercising its powers.

- Article 70

Tasks of the Board

The Board needs to monitor and

ensure correct application of this Regulation, advise the Commission, issue

guidelines, recommendations, and best practices, etc.

- Article 71

Reports

The Board will write an annual public report on the protection of natural persons with regard to processing.

- Article 72

Procedure

The Board will consider decisions by a majority vote and adopt decisions by a two-thirds majority.

- Article 73

Chair

The Board elects a chair and two deputy chairs by a majority vote. Terms are five years and are renewable once.

- Article 74

Tasks of the chair

The Chair is responsible for setting up Board meetings, notifying supervisory authorities of Board decisions, and makes sure Board tasks are performed on time.

- Article 75

Secretariat

The European Data Protection Supervisor will appoint a secretariat that exclusively performs tasks under the instruction of the Chair of the Board, mainly to provide analytical, administrative, and logistical support to the Board.

- Article 76

Confidentiality

Board discussions are confidential.

Chapter 8 Remedies, Liability, and Penalties

This chapter covers the rights of data subjects to judicial remedies and the penalties for controllers and processors.

- Article 77

Right to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority

Every data subject has the right

to lodge a complaint with a supervisory authority.

- Article 78

Right to an effective judicial remedy against a supervisory authority

Each natural or legal person has the right to a judicial remedy against a decision of a supervisory authority.

- Article 79

Right to an effective judicial remedy against a controller or processor

Each data subject has the right to a judicial remedy if the person considers his or her rights have been infringed on as a result of non-compliance processing.

- Article 80

Representation of data subjects

Data subjects have the right to have an organization lodge a complaint on his or her behalf.

- Article 81

Suspension of proceedings

Any court in a Member State that realizes proceedings for the same subject that is already occurring in another Member State can suspend its proceedings.

- Article 82

Right to compensation and liability

Any person who has suffered damage from infringement of this Regulation has the right to receive compensation from the controller or processor or both.

- Article 83

General conditions for imposing administrative fines

Each supervisory authority shall ensure that fines are effective, proportionate, and dissuasive. For infringements of Articles 8, 11, 25 to 39, 41, 42, and 43 fines can be up to $10,000,000 or two percent global annual turnover. For infringements of Articles 5, 6, 7, 9, 12, 22, 44 to 49, and 58 fines can be up to $20,000,000 or four percent of global annual turnover.

- Article 84:

Penalties

Member States can make additional penalties for infringements.Chapter 9 Provisions Relating to Specific Processing Situations

This chapter covers some exceptions to the Regulation and enables Member States to create their own specific rules.

- Article 85

Processing and freedom of expression and information

Member States have to reconcile the protection of personal data and the right to freedom of expression and information (for journalistic, artistic, academic, and literary purposes).

- Article 86

Processing and public access to official documents

Personal data in official documents for tasks carried out in the public interest may be disclosed for public access in accordance with Union or Member State.

- Article 87

Processing of the national identification number

Member States can determine the conditions for processing national identification numbers or any other identifier.

- Article 88

Processing in the context of employment

Member States can provide more specific rules for processing employees’ personal data.

- Article 89:

Safeguards and derogations relating to processing for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes

Processing for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes is subject to appropriate safeguards (data minimization and pseudonymization).

- Article 90

Obligations of secrecy

Member States can adopt specific rules for the powers of the supervisory authorities regarding controllers’ and processors’ obligation to secrecy.

- Article 91

Existing data protection rules of churches and religious associations

Churches and religious associations or communities that lay down their own rules for processing in order to protect natural persons can continue to use those rules as long as they are in line with this Regulation.

Chapter 10 Delegated Acts and Implementing Acts

- Article 92

Exercise of the delegation

The Commission has the power to adopt delegated acts. Delegation of power can be revoked at any time by the European Parliament or the Council.

- Article 93

Committee procedure

The Commission will be assisted by a committee.

Chapter 11 Final Provisions

This chapter explains the relationship with this Regulation to past Directives and Agreements on the same subject matter, requires the Commission to submit a report every four years, and enables the commission to submit legislative proposals.

- Article 94

Repeal of directive 95/46/EC

1995 Directive 95/46/EC is repealed (The old personal data processing law).

- Article 95

Relationship with Directive 2002/58/EC

This Regulation does not add obligations for natural or legal persons that are already set out in Directive 2002/58/EC (has to do with the processing of personal data and the protection of privacy in the electronic communications sector).

- Article 96

Relationship with previously concluded Agreements

International agreements involving the transfer of data to third countries or organizations that were setup before 24 May 2016 will stay in effect.

- Article 97

Commission reports

Every four years the Commission will submit a report on this Regulation to the European Parliament and to the Council.

- Article 98

Review of other Union legal acts on data protection

The Commission can submit

legislative proposals to amend other Union legal acts on the protection of

personal data.

- Article 99

Entry into force and application

The Regulation applies from 25 May 2018.

1 What’s Data Privacy Law in Your Country?

When creating the content for your website, legal notices like your Terms of Service, Cookie Notifications, and Privacy Policies are often an afterthought.

Blog posts might be a lot more fun to write, but neglecting to give your readers the right information can get you in legal trouble.

You might think only the giants like Google and Facebook really need a Privacy Policy, or websites that handle data like credit card numbers or social security numbers.

In reality, many of the countries with modern data privacy laws have rules in place for handling any kind of information that can identify an individual or be used to do so.

Even if you just collect names and email addresses for your newsletter, display a few Google Ads on your site, or use browser cookies to get traffic analytics, you’re required by law in many jurisdictions to inform your audience of certain facts and policies of your website.

If you don’t, or if you just use a generic Privacy Policy template that doesn’t accurately reflect your policies, you could be threatened with legal action from your website visitors or your government, and end up paying huge fines or legal fees – or even face jail time.

Why take the risk? Save yourself the time, trouble, and expense of legal consequences, and get up to speed on your country’s privacy policy laws right here.

2 Privacy Laws by Country

Laws regarding privacy policy requirements for websites are generally included in information privacy or data protection laws for a country. These laws govern how information on private individuals can be used. A relatively recent legal development, privacy laws have now been enacted in over 80 countries around the world.

Argentina

Argentina’s Personal Data Protection Act of 2000 applies to any individual person or legal entity within the territory of Argentina that deals with personal data. Personal data includes any kind of information that relates to individuals, except for basic information such as name, occupation, date of birth, and address.

“Personal data” can, however, include the use of browser cookies. If you track your visitors using an analytics service, or if you use an ad network that uses cookies, then these policies will apply to you.

There is some legal disagreement about whether IP addresses count as personal data, with experts on both sides of the issue. To be on the safe side, you likely want to obtain consent if you collect any information regarding an individual’s IP address, or use cookies in any way.

According to Argentina’s laws concerning privacy, it’s only legal to handle or process personal data if the subject has given prior informed consent. Informed consent means you must tell them the purpose for gathering the data, consequences of refusing to provide the data or providing inaccurate information, and their right to access, correct, and delete the data. Also, any individual can request deletion of their data at any time.

Australia

Australia’s Privacy Principles (APP) is a collection of 13 principles guiding the handling of personal information. According to these principles, you must manage personal information in an open and transparent way, which means having a clear and up-to-date Privacy Policy about how you manage personal information.

Privacy Policies, according to Australian law, need to detail why and how you collect personal information, the consequences for not providing personal information, how individuals can access and correct their own information, and how individuals can complain about a breach of the principles.

One of the roles of the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) is to investigate any privacy complaints about the handling of your personal information. Anyone can make a complaint to the office for free at any time, and the office will investigate as soon as possible.

In order to avoid complaints about your handling of personal information, it’s important to have a clear and accurate Privacy Policy that includes all the requirements laid out by the APP.

Brazil

Brazil passed the Brazilian Internet Act in 2014 which deals with policies on the collection, maintenance, treatment and use of personal data on the Internet.

Any Brazilian individual and legal entity must obtain someone’s prior consent before collecting their personal data online, in any way. Consent can’t be given by those under 16 years old, and from 16 to 18 years old they must have assistance from their legal guardian to give consent. So, before collecting any information, be sure to ask whether the user is over 18 years of age.

It also states that your terms and conditions about how you collect, store, and use personal data need to be easily identifiable by your users, which means having an accurate and easy to understand privacy policy.

Canada

Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Data Act (PIPEDA) governs how you can collect, store, and use information about users online in the course of commercial activity. According to the act, you must make information regarding your privacy policies publicly available to customers.

Your Privacy Policy should be easy to find and to understand, and be as specific as possible about how you collect, handle, and use information.

For more information, check out the Privacy Toolkit and Fact Sheet from the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada.

Chile

According to Chile’s Act on the Protection of Personal Data, passed in 1998, personal data can only be collected when authorized by the user. You also need to inform users of any sharing of information with third parties (such as if you have an email newsletter provider like MailChimp or AWeber that you share emails with).

However, you don’t need to get authorization for basic information like a person’s name or date of birth, or if you’re only using the data internally to provide services or for statistical or pricing purposes.

Colombia

Colombia’s Regulatory Decree 1377 states that you must inform users of the purpose their data will be used for, and you can’t use the data for any other purpose without obtaining consent.

Privacy Policies must include a description of the purpose and methods for processing data, the users’ rights over their data and the procedures for exercising those rights, and identification of who is responsible for handling the data.

Czech Republic

Act No. 101/2000 Coll., on the Protection of Personal Data governs how personal data is collected by anyone in the Czech Republic.

If you collect any kind of information relating to an identifiable person, you need to inform them of the purpose for collecting the data and the way it’s collected, and obtain their consent.

Denmark

Denmark passed the Act on Processing of Personal Data in 2000. The Danish Data Protection Agency supervises and enforces the privacy laws. If they discover violations of the law, they can issue a ban or enforcement notice, or even report the violation to the police.

According to the law, personal data can only be collected if the user gives explicit consent. Also, a company can’t disclose personal information to third parties for the purpose of marketing without consent.

Estonia

The Personal Data Protection Act of 2003 in Estonia states the personal data needs to be collected in an honest and legal way. You must obtain consent from users, and inform them of the purpose of collecting their data, and only use it in that way. A Privacy Policy is the key way to inform users.

European Union

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) became enforceable in 2018 and is to date the most robust privacy protection law in the world. It has since inspired other laws around the world to up their requirements and has inspired the creation of new laws.

The GDPR protects people in the EU from unlawful data collection or processing and works to increase consent requirements, provide enhanced user rights and require a Privacy Policy that’s written in an easy-to-understand way.

Finland

The Personal Data Act governs the processing of personal data gathered in Finland, where privacy is considered a basic right. Anyone who gathers personal data in Finland must have a clearly defined purpose for gathering the data, and may not use it for any other purpose.

Personal data can only be gathered after obtaining unambiguous consent from the user.

The controller (the person or corporation collecting the data) of the collected data also needs to create a description of the data file, including their name and address and the purpose for collecting the data. This description needs to be made available to anyone.

There are also special restrictions that apply if you’re collecting data for the purpose of direct marketing or other personalized mailing related to marketing. Your database must be limited to basic information and contact information (no sensitive data can be collected).

France

The Data Protection Act (DPA) of 1978 (revised in 2004) is the main law protecting data privacy in France. The Postal and Electronics Communications Code also touches on the collection of personal data when it’s used for sending electronic messages.

The DPA applies to the collection of any information that can be used to identify a person, which is very broad in scope. The rules apply to anyone collecting data who is located in France or who carries out its activities in an establishment in France (such as if your hosting server or other service provider related to collecting or processing data is located in France). This is why the French Data Protection Authority was able to fine Google for violating their privacy laws.

Before automatically processing any kind of personal data, you must obtain the consent of the subject, and inform them of a number of things, including the purpose of the processing, the identity and address of the data controller, the time period the data will be kept, who can access the data, how the data is secured, etc.

Germany